Spinners of Fate with One Broken Face

2022.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, the three Fates Parcae were the female personifications of destiny who directed the lives (and deaths) of humans and gods. Their technology of choice were simple threads, woven and spun into intricate lattices that controlled the fate of the world. A material so meager could change the trajectory of society and culture for millennia.

We find ourselves obsessed with consuming new technologies, especially personal computing devices like smartphones, laptops and tablets. Social media and the selfie camera provide new ways for the individual to present their image to the world, and the result is mass obsession with capturing one’s face. The personal computer becomes a personal mirror and the essence of a person becomes distilled into a single frame. But all mirrors eventually break, revealing a clearer sense of how our understanding of the self has changed for better or worse.

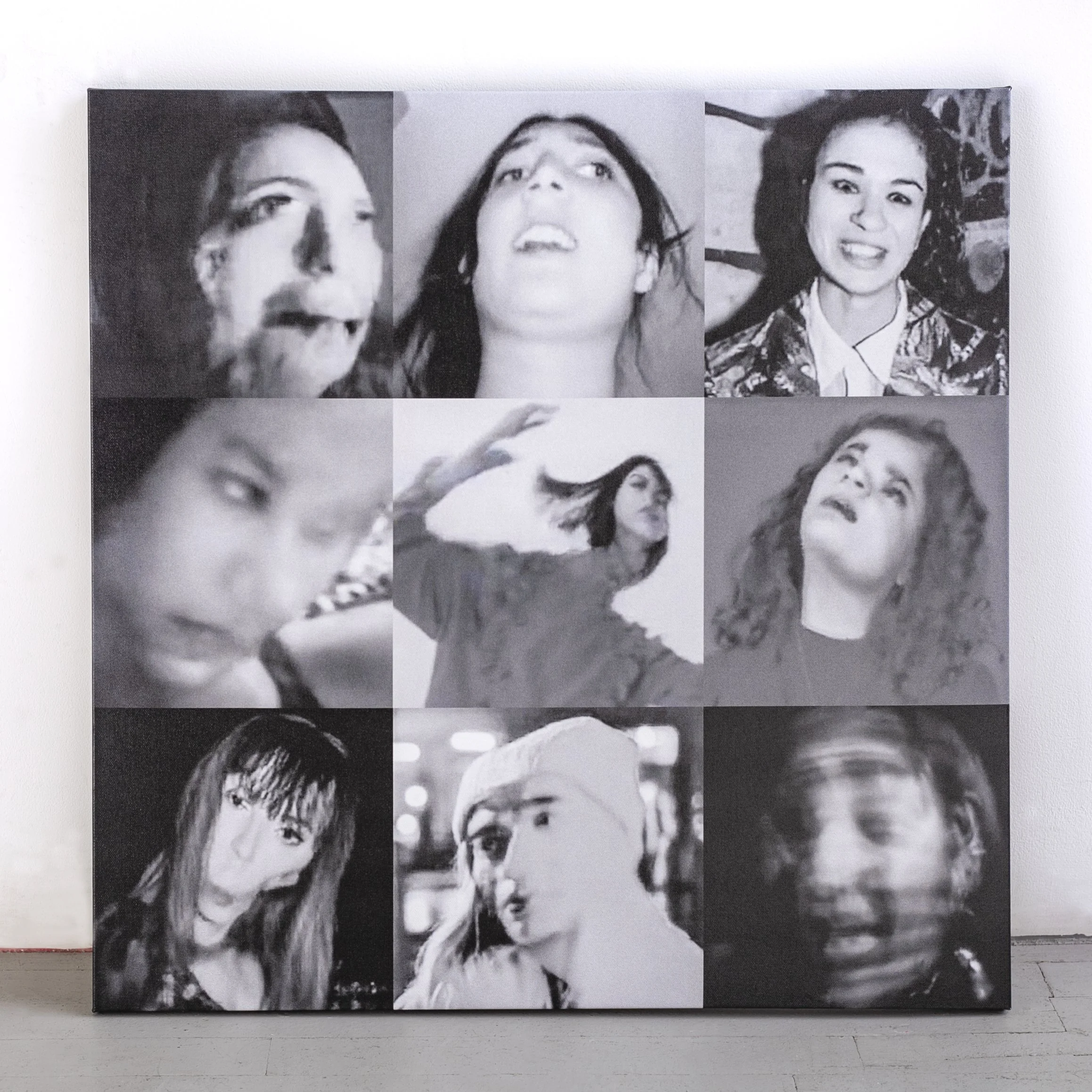

In Spinners of Fate With One Broken Face, I code low-res deep fake videos using a Python script called First Order Motion Model. I shoot photographs of my friends and then feed motion information from a video of my own face into the photograph, so that my facial movements map on to their faces. So if I raise my eyebrows, my subjects raise their own. If I twist my neck, their faces turn sideways.

Popular culture typically views deep fake technology as seamless and convincing, but the fake videos you see of politicians or celebrities take weeks and serious expertise to perfect. First Order Motion Model is rudimentary, so it reveals the drawbacks of the technology. Individual frames glitch and decouple the appearances of the subjects. They transform into ghastly ghouls and sinister puppets with elongated necks and broken skulls.

With this series, I explore internet culture's obsession and self-preservation of the face. Presented in a 3x3 grid akin to the Instagram profile feed, these images point to social media's command over contemporary representation and distribution of the self.

The selfie camera and social media provide new ways for individual expression, but should we question what lies below the surface of these carefully-curated pixels? How has the selfie camera morphed our understanding of our bodies, and how do we use this device to reject the aspects of ourselves that we don’t like? More-so, how has social media altered our society for the worse, and what do our true selves look like beneath the facade it builds?

As we become evermore addicted to platforms, is this how technology sees us, as disturbed, bug-eyed succubi looking for fulfillment inside a screen? At what point will our personal mirrors entrap our souls? And then how do we break out?